What follows is the story of my Australian cousin George. It's a tale of derring-do and survival that crossed many borders; George was in turn brave, reckless, audacious, and enterprising––whatever was needed. He is the reason Ken and I went to visit Australia in the first place. We met George and his wife Nelly when they visited us in Massachusetts years ago, and we fell in love with them both.

But why write this story now? I was looking for some old photos, and remembered that I had rough notes about George’s life, but never did anything with them. I thought I’d give them another look. Maybe the real reason is that sometimes burying oneself in memories of another era instead of this one is a welcome distraction.

But why write this story now? I was looking for some old photos, and remembered that I had rough notes about George’s life, but never did anything with them. I thought I’d give them another look. Maybe the real reason is that sometimes burying oneself in memories of another era instead of this one is a welcome distraction.

MY COUSIN GEORGE

What follows is based upon written notes assembled by George’s son-in-law Greg Uhe from conversations he had with George and my own conversations with George plus a few additions of my own.

GOOD TIMES BEFORE THE WAR

My cousin was born George Rudolf Drobenko on May 5, 1926, in Russia, or what was then Soviet Russia, and is now Ukraine. His father, Rudolf Drobenko, from whom George undoubtedly gained his middle name, was Russian Orthodox insofar as he was at all religious, and a criminal lawyer by profession. The Drobenko family apparently had roots in the area, given that his paternal grandfather had been the Mayor of the city of Kharkiv, second in size only to Kyiv, Ukraine’s largest city. There was an Austrian connection as well in the family lineage, as his paternal grandmother was from Klagenfurt. A more recent Austrian addition to the Drobenko family was George’s mother, Ella Gabron.

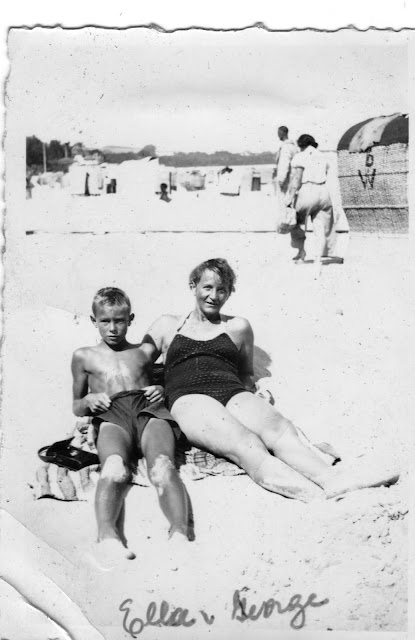

|

| This photo was in my parents' photo album. My father always spoke warmly of George. As a child he seemed a distant figure to me. I never imagined I would ever meet him. |

Ella was one of my father’s four sisters. All four had names that as a child I used to enjoy reciting as fast as I could: Ady, pronounced Ah-dee, for Adela, Ella, Irma and Ida. Ella was by far his favorite. In 1956 I met Ady who lived then in central Germany, in the middle of nowhere, and Irma, in Vienna. Both were widows. I sensed Irma liked to play the grand lady, but I don't remember much about Ady, perhaps because at seventeen I was more interested in her two teenaged daughters. It was not until 1989 that Ken and I found Ida and her husband Hans in a nursing home in the outback in Australia near Cairns, both well into dementia by then.

Ella was from Steiermark, a region of Austria that includes the city of Graz, and like most Austrians, she was Catholic, although religion seems to have played little or no role in the family's life. Ella had met Rudolf Drobenko when she was a nurse during the first World War. He was one of the wounded soldiers she had cared for. A meeting like this, nurse and wounded soldier, could have been the beginning of a wildly romantic tale. And maybe for a time it was.

The family remained in Russia/Ukraine for only three months after George was born before moving to Sopot, Poland, a town on the Baltic Sea where George fondly remembered going to the beach as a young boy. By the time he was eight or nine years old he was sent off to boarding school where he saw his parents and aunt only in vacation periods.

|

| Left to right: Irma (?), Ida, Ella, and George's father Rudolf holding George. |

Looking back, George recalled being “above average in languages,” perhaps hinting that his performance in the other subjects was less than memorable. Facility in languages may have been helped along by the fact that his family spoke both German and Polish at home, and his mother's insistence that he learn French for, as he put it, “snobbish reasons,” French still being the language of the upper crust in those days. For his part, George’s father insisted on their speaking Russian. George liked school; that is, he liked being at school having fun. He recalled being a “naughty boy” and often “wagged school” (played truant).

The family lived well. They had servants, owned two cars, unusual at the time, and employed a chauffeur. Skiing holidays were part of their way of life. Eventually they moved to Germany, settling in the Duchy of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, a province near the Polish border that was later absorbed into yet another province. Around this time George's father became a naturalized German citizen. It was an interesting time, to say the least, to have chosen to become a German citizen. By this time Hitler’s party was either gaining power or–assuming this citizenship occurred after 1933–Hitler had already become Chancellor. The family was well-connected. George said that his father became Governor of an area in Poland when it came under German occupation. His best friend’s father was Governor of another part of Poland.

If Rudolf indeed governed a section of Poland–I have been unable to find a list of the Governors who served under Hans Frank, Governor of the entire Polish occupation–this would place him there following 1939 when the German occupation began. Rudolf would have reported to Frank, who in turn reported directly to Hitler. Some three million Jewish Poles were sent to extermination camps from German-occupied areas in Poland between 1939 and 1945. Hans Frank was executed at Nurnemberg for crimes against humanity after the war.

|

| From my parents' album: George, his father and mother on a ski holiday. |

HAVING FUN, UNTIL THE WAR BEGINS

By now George was a teenager, and accordingly was sent to an upper level boarding school. This school was in Zakopane, Poland, perhaps selected because it catered to the wealthy, and perhaps also because it was in an area much favored by important members of the Gestapo. Zakopane is a resort town in the Tatra mountains, today, as then, a popular access point for skiing, climbing, and hiking. Certainly an appealing location for a school. George’s regular studies again included languages: English, French, Latin and German. (Yet only a few years later, at a crucial moment, the English language would forsake him and he would be unable to speak a word of it.) But studies hardly made up the whole of his school experiences, and he early on established a reputation as a rebel. This was where he first took up smoking, which would become a lifelong habit. Good-looking and wildly charming, he had no trouble getting involved with girls from a nearby school. It was here he learned to become a master of escape. In one incident he was caught hiding under a bed, with a girl. He fled a room by letting himself out through a window and lowering himself by rope. Worse yet, he copied an exam. He was caught more than once. Thanks only to his father’s lofty position he avoided being expelled. There was also skiing on hand nearby, and on skiing holidays his Aunt Irma would come to visit. Alas, he recalled, when she was visiting she would “spoil things.” Although it's not clear what she spoiled, it may not be hard to imagine. Despite these distractions George managed to stay for three years, going home only for the routine Christmas and June holidays. At last the war arrived at the school’s door. In 1944 the school was evacuated and placed under Russian occupation. His family moved George to a boarding school in southern Germany, in Bavaria.

Now in Bavaria, far to the south, it was easier for him to visit his mother who by this time was staying with his grandmother in Schönberg, presumably because his father was caught up in the machinations of the war which, by that time, was going badly for Germany. Schönberg is in the Sudentenland territory that had been annexed by Hitler at the start of the war, and was thus incorporated into wartime Germany. This was the town (then Austrian) where my father, born in Vienna in 1899, lived as a young boy. In 1945 Schönberg would be liberated by the Russian Army, and all Germans living there deported to parts of Bavaria and Austria. This was how my grandmother and Aunt Irma and family came to live in Vienna where my father helped them buy an apartment. The town of Schönberg, now called Šumperk, the Czech word for Schönberg or “beautiful mountain,” became part of Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic). More of that later.

A TURNING POINT

|

| From my parents' album. |

Perhaps also around this time he came to fully understand that his father, holder of a high govermental position with Hitler in power, would have to have been a Nazi. Was a Nazi. It may be that George had known or suspected this all along. The estrangement from his father may have begun with that awareness, but surely it intensified when he saw with his own eyes that his father had betrayed his mother. This may have been the moment when he decided he no longer wanted to be associated in any way with his father. He no longer wanted to be known by his father’s name. He officially changed his name from Drobenko to his mother’s maiden name. From now on he would be known as George Gabron.

George was nineteen in 1945, a momentous year. As the year began, the Germany army was in retreat, and by April Hitler was in his Berlin bunker. Much of Austria and Germany was in ruins. In May Germany surrendered. Somehow George managed to complete his final year of school despite having missed much of it, what with playing billiards and staying out all night, not to mention the war all around him. Still, school was done with, and beyond the school a changed world awaited. After graduating he went straight to Prague, now under Russian occupation, to join his mother who was living there, by herself, in a hotel. His father was missing. But missing how? Was he on the run? Prague wasn't safe, and plans were made to leave. But instead they delayed. His mother may have counted on his father showing up. A meeting may have been prearranged.

They stayed too long. It was in Prague that his mother was killed. She was shot in front of George by Czech partisans. One of the Czechs handed George his mother's jewelry. He ran. This is how I heard the story from George. There were no details. Maybe when you tell someone a long story that includes an event like this you can't stop to fill in the small often telling details. When you're the listener, you may not feel you can ask about those details. Since those of us who listened didn't probe, we were left to wonder. We might picture soldiers bursting into their room in the middle of the night. Or was it daytime? Maybe Ella and George were taken someplace, maybe only downstairs. Was Ella singled out? Or was she one of many? Were they looking for George’s father? (He would likely not have been unknown.) We know they weren’t interested in money, as George said it was Czechs who handed George his mother’s jewelry. But how did they get the jewelry? Was it hidden somewhere? Or was Ella wearing it? Why did they allow George to get away? Did they feel sorry for him? (Hey, give him the jewelry, he’s just a kid!)

|

| George's mother Ella, a photograph taken before she was married. |

The answers to some of these questions lie somewhere in the chaos that immediately followed the end of the war. George’s grandmother, aunt and family had made it to Vienna. But Czechoslovakia was not safe.

In 1945 the war had barely ended when Czechoslovakia began to expel the two million Germans who lived in Sudetenland. The expulsion took on almost hysterical urgency on July 31 when a munitions depot exploded in the Czechoslovakian town of Ústi nad Labem, about forty miles from Prague. Rumors began to spread that the Germans who lived there were responsible. Whether or not they were, what followed was a massacre. Some two thousand or more Germans were killed that day in Ústi nad Labem. Those responsible were said to have been a combination of Revolutionary Guards, a post-war Czech paramilitary, along with Russian and Czech soldiers, and a few hundred Czech civilians who had come there by train from Prague to take part. It is not hard to imagine the desires for revenge that raged throughout Czechoslovakia. Many thousands of Czechs had been killed by the Nazis, so many that it dwarfed the number of killings that took place that day and the many days afterwards. Despite pleas by the Allied Powers that expulsions be humane, orderly, and non-violent, they were often rough, fed by hatred, a need for revenge, and despair.

With the death of his mother, George had nowhere to hide, no one to turn to. He fled, he ran, with that jewelry, and with it and some luck he was able to buy his way out of Prague. He paid a Frenchman who finagled to get him, along with other refugees, on a train to Pilzen, a city to the west of Prague. With the aim of somehow getting to London he pretended to be British, even though he couldn’t actually speak English. (Where were those language lessons now!) Together with some actual British people he went first to Paris and from there flew to London. In London he was quickly discovered not to be in the least British, and was jailed for a week before being sent right back to Paris.

Once back in France he found himself broke, without money and without food. Desperate, he found work in US military camps where at least he was able to get meals. He found some work in a knitting factory, but that didn't last long. He went back to Paris and scraped together enough money to find an apartment there. Somewhere along the way he happened to meet a French crook, a fortuitous meeting that opened the door to other ways of making money. He began to smuggle cigarettes, nylon stockings, coffee and cloth, all in huge demand after the war. He would buy from Americans and sell to the French. It was a lucrative business. He managed well enough in this occupation to holiday in Nice and Monte Carlo.

|

| George's Paris apartment. Stephanie Gabron, his granddaughter, located it when she was in Paris in 2012. |

George arranged to visit Vienna, then divided into sectors controlled by Allied and Russian forces, to visit his grandmother, Aunt Irma, her son Gernod and daughter Inge (also my cousins). "Arranging" was a complicated business. He disguised himself as an American soldier, hoping no one would speak to him and discover he wasn’t actually American, not to mention his lack of ability to speak American English or any other kind. The apartment** my father had bought in Vienna for his mother had the misfortune to be in the Russian-controlled zone. The Russians, or rather Soviets, as they were known at the time, were not the choicest occupiers, as they were more interested in stripping the city of infrastructure, and the soldiers themselves had more interest in stripping any items that they thought were of value. George arrived in Paniglgasse with packages of food that they desperately needed. For everyone the goods of daily life were in short supply. I remember hearing a story of someone having being shot in a dispute over a can of peas. Fuel as well as food was scarce. People hiked out of the city to the countryside if they could to buy potatoes and vegetables from farmers. Most had only basic rations. My mother regularly sent them huge packages of food in cartons that she wrapped with old pillow cases that she sewed on so they couldn’t easily be opened up before they arrived. “Care packages.”

|

| The first three or four windows on the second floor are the Vienna apartment. |

|

| Ken and I visited No. 9 Paniglgasse in 2012. I had last seen the apartment in 1956. |

George returned to Paris. By 1946 he was smuggling in a major way. Having accumulated some 100,000 French francs, he hoped to go to Australia where another of my father’s sisters, his Aunt Ida, had emigrated years earlier, following her husband Hans Dolleschel who went there in search of a fortune. In order to move to Australia one needed to have an Australian sponsor. Ida and Hans lived in what was then a remote area near the Daintree River north of Cairns. They had no children. She was cool to the idea of sponsoring him and made no offer. Frustrated, George continued with his various enterprises.

He would go to Hanover, Germany, to buy cheap stamps and re-sell them in Paris, but he was caught red-handed in Kassel, Germany, with those stamps as well as a false ID (he used a number of aliases) that resulted in two weeks of jail time. Undaunted, he returned to Paris, where pressing financial need prompted him to resume smuggling. In Brussels he found he could buy just about anything that would be easy to resell. On one of those Belgian trips he was nearly captured when a train he was on was raided. He leapt onto the roof of the train. Luck was with him, and he evaded capture. When smuggling was good and he had money, he lived well, even going so far as to hire an expensive car. But there was always risk, and plenty of it. While in Paris he was raided yet again, and escaped again; this time to get away he and a friend had to jump from rooftop to rooftop. Safety continued to elude him. While he was walking very near the border another time, wearing a black coat in the faint hope of blending into the darkness, he was spotted and locked up in Lille for several weeks in what he remembered were “terrible conditions.” Worst of all, he lost all his money.

ESCAPE TO AUSTRALIA

Again he wrote to Aunt Ida in Australia to please send him money. Then he waited. And waited. At long last, and probably with reluctance, she agreed to sponsor him so that he could come to Australia. At last! He didn’t hesitate. Come to Australia he did, arriving by ship, then made his way overland to Daintree. In Daintree Aunt Ida and Hans had a small self-sufficient plantation with windmill, a water supply, electricity, and access to the Daintree River, where they grew all manner of tropical fruits, coffee and cocoa, raised turkeys, chickens and peacocks. Even in as late as 1989 when I was in Daintree there was not much there: a few stores, several wooden buildings, rain forest all around, the river with its enormous crocodiles, and a ferry link to the single road north. The place may have offered safety and shelter, but it did not feel like home to George. There was a decided lack of warmth. Ida and Hans did not welcome him as a close member of the family, much less an adopted son. Maybe they relished their remoteness and the lack of other society. At any rate, he knew this was not the right place for him. He lived with Ida and Hans for as long as he could endure it. When it became unbearable, he made yet another escape, his last escape, and lit out for Melbourne, nearly 3,000 kilometers away.

The rest is history. That is to say, it was the beginning of a new kind of life, the one that we all know about. It was also the end of his misadventures. Luck with with him once again, as it was in Melbourne where George met Nelly. Nelly had an interesting story of her own about how she came to be in Australia. She been deported by the British with her family from Palestine. Her family had been part of a German colony that called themselves Templars, a group that had begun to emigrate to farm in the Holy Land in the 1860's. Now regarded as enemies of the Allies, some 500 were sent to Australia. Nelly was interned in a camp outside of Melbourne until the war’s end. On release, internees were given $15 and a choice: get sent to Germany, or remain in Australia. Never having lived in Germany, for Nelly and her family the answer was obvious. As for George, he had to find a way to make a living in Melbourne, having up to now had no time for learning a profession, and no marketable skills. So he started a painting business. He and Nelly were married. And, in time, George and Nelly became the progenitors of a virtual dynasty of Australians who are now to be found in Melbourne, the Sunshine Coast, and western Australia. The third generation is already arriving.

|

| George and Nelly at the time of their marriage. I took this photo from one Nelly had framed in her home on a visit in 2010. |

But I’m jumping ahead. One day after the war Aunt Irma spotted a familiar figure getting on a train in Vienna. It was George’s father! He was alive. Where had he been all this time? What had he been doing?She went over to him and she gave him George’s address in Australia. She must have questioned him, but nothing about their conversation seems to be known. Not long after, George received a letter from his father, the only news he had had of him in years. His father wrote that he planned on coming out to Australia to visit. However, it was a visit that never happened. One night in 1950 Nelly was waiting to meet George at a dance at the St. Kilda town hall in Melbourne. When George didn’t come on time she thought for sure that he had stood her up. He finally did arrive, very late. He had just gotten word, he told Nelly, that his father had died. How would George have felt about seeing his father again, I wondered. He had told me how much he hated his father, a Nazi, a betrayer. He didn’t care if he ever saw him again. Maybe it was better this way.

EPILOGUE

One day a French woman knocked on the Aunt Ida’s door in Daintree and asked for George. Who could she have been? Surely there was a story here.

George never quit his smoking habit. It very likely contributed to his untimely death. He died a year or so after our first visit to Australia in 1989. He was only in his early sixties.

NOTES

*My father John (Hans) Gabron came to New York City from Rio de Janeiro in the late 1920's, having left Austria a few years earlier. He hadn’t seen George since George was a young boy, not until he and Nelly visited my parents in New York City in the 1980’s and then came to see us in Lexington, Massachusetts. That was when I first met George. Although my father had visited his sisters in Europe immediately after the war and several times in later years, he never saw Ella again, and George had long since escaped to Australia. His only contact with his sister Ida in Australia was via a rare letter. Even then I dimly recall her being thought of as odd. I never met my Austrian grandmother.

**No. 9 Paniglgasse: It was my understanding that my father bought the apartment on Paniglgasse for his mother after they were forced to leave Schönberg. The apartment was shared then and after her death by Aunt Irma (Garo), her son Gernod, and his wife Lisalotte. (Daughter Inge decamped for the US shortly after the war to marry an American soldier whom I later heard she divorced.) I never met my cousin Gernod who drowned in the Danube (ruled an accident), but I visited the apartment in 1956 and again in 2012 when Lisalotte lived there alone. In 1956 evidence of war damage was still obvious. Across the street from No. 9 Paniglgasse was what had been a school building. From the apartment I could see into the school windows where toilet bowls were piled up to the ceiling. I was told that they were leftovers Soviet soldiers had been unable to take with them when the occupation ended.